|

The day after being sentenced the Kid was loaded into a coach for the

five-day journey to Lincoln, and again was told if there were a rescue

attempt or a lynch mob, his guards would kill him first. There were seven

heavily armed men in the escort, including Bill Mathews, John “King of the

Rustlers” Kinney, and the burly Bob Olinger. All three

fought on the Dolan side and were prejudiced against the Kid -Olinger in

particular. The Kid and Olinger had a mutual hatred because Olinger shot

John Jones, a friend of the Kid’s, in cold-blood. Afterwards, Olinger

learned the Kid wanted to kill him in revenge. Their resentment for each

other sparked the bitter

animosity. During the long trip to Lincoln, Olinger took advantage of the

Kid’s helpless situation by taunting and provoking him to escape. The Kid

kept his sense of humor and ignored him. It was a tense trip. If the Kid so

much as made a wrong move, his guards would have shot him, but sources say

he remained in good spirits.

|

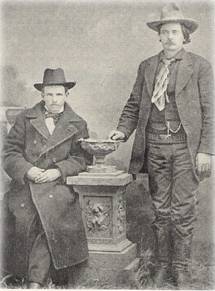

James Dolan (seated) & Bob Olinger (1879)

Photo from R.G. McCubbin Collection |

Finally on April 21st, the Kid arrived in

Lincoln. There was no suitable jail, so the Kid was confined in a backroom

adjoined to Garrett’s office in the old two-story Murphy store, which was

now a courthouse. He was to remain handcuffed and shackled at all times and

was either chained to the floor or a line was drawn across the room, which

he was forbidden to cross or he would be shot. To eliminate any chance of escape,

Garrett had two of his deputies remain with the Kid in the room as a 24-hour

gurad; the two guards were Olinger and James Bell.

|

|

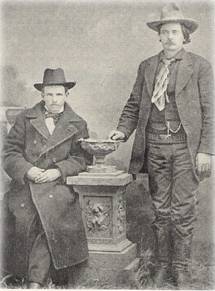

The Courthouse in Lincoln (late 1880s-90s)

Photo from R.N. Mullin Collection

The staircase from the balcony was not added until much later after the

Kid's escape.

Billy the Kid was confined on the second story, front left corner room.

The side window you see is where the Kid shot Olinger. |

|

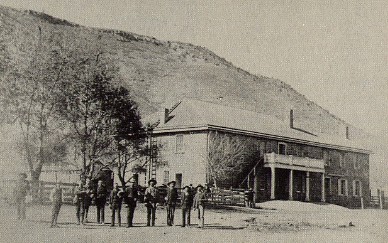

Lincoln courthouse as it looks today.

Webmaster's photo (2000)

Not much as changed, other than the roof and another staircase added to the balcony.

The once hard to see scrawny tree, as seen in the first photo, has now grown so large it blocks out

the view

of Billy the Kid's room. |

Any other prisoner would have given up hope and come to grips with his fate,

but not the Kid! His mind was still at work on escaping, but time was

running out. The Kid had to act fast on the first opportunity, but he had to

wait patiently for the right moment. If he made the slightest wrong move or

even looked as if he was thinking of escape, Olinger would split him in two with his shotgun, which he

teased the Kid with everyday.

About a week after the Kid's arrival, Garrett had left Lincoln to collect

taxes, leaving his two guards in charge. On April 28th, at noon, with only two

lawmen in the whole town, the Kid saw his golden opportunity. He knew it was Olinger’s turn to take the other prisoners, who were also confined at the

courthouse, across the street for lunch at the Wortley Hotel (the Kid ate

his meals in his room), which meant only Bell would be at the courthouse to

guard him. The Kid knew, out of his two guards, it would be best to make his

move on Bell who was easy-going and not on a power trip as Olinger was. As

soon as Olinger was long gone with the other prisoners and eating his meal,

the Kid then made his move. The only time the Kid was allowed to leave the

room was for visits to the privy (outhouse), so he asked Bell to take him outside.

What happened next is a subject for debate; one version, which seems the

more popular, is that the Kid retrieved a gun that was hidden in the privy

by a friend. As he entered the courthouse and climbed the stairs and

reached the top, he turned around with the gun drawn and told Bell to

surrender. Bell panicked and spun around to run down the stairs leaving the

Kid with no choice but to shoot him.

The

next version, which I find the most logical, comes from the Kid himself.

After his escape, the Kid told his friend, John Meadows, whom he visited

right after he left town a free man, that he slipped his small hand out of

one of the cuffs, whacked Bell over the head and jerked Bell’s revolver out

of the holster and told him to throw up his hands. But instead, Bell turned

and ran down the stairs and the Kid shot him. This then explains the two

gashes found on Bell’s head, the scuffling sound which was heard from the

groundskeeper, Gottfried Gauss, who was standing outside by the door and

caught the dying Bell as he rushed into his arms, and lastly, it explains

why Bell just ran instead of pulling out his own gun and shooting as he

fled. After all, Bell was a veteran lawman, and couldn’t have been that

timid (or stupid).

At the restaurant, Olinger heard the shots fired and darted outside. As he

rounded the gate into the yard of the courthouse, he heard a familiar voice,

“Hello Bob.” he looked up and saw the Kid at the window with his own shotgun

pointing right at him. At that moment the startled groundskeeper came

running from behind the building, saw Olinger and yelled out, “The Kid

killed Bell!” Olinger then replied, “Yes, and he’s killed me too.” The Kid

then let Olinger have it with both barrels and his tormentor and killer of

his friend John Jones, fell dead.

Next, the Kid had Gauss toss him up a small pick that was lying on the ground

and told him to saddle a horse. The townspeople made no move to interfere as

the Kid took his sweet time in leaving. After using the pick to free only

one leg from the shackles, the Kid went out on the balcony and saw that a

small crowd had gathered and was watching from from across the street; a

witness’s statement of what the Kid said would verify how he killed Bell:

“He stood on the upper porch in front of the building and talked with the

people who were in Wortley’s, but he would not let anyone come towards him.

He told the people that he did not want to kill Bell, but as he ran, he had

to. He said he grabbed Bell’s revolver and told him to hold up his hands and

surrender and that Bell decided to run and he had to kill him. He declared he

was ‘standing pat’ against the world and while he did not wish to kill

anybody, if anybody interfered with his attempt to escape, he would kill

him.”

After arming himself with revolvers and a rifle, he went down the stairs and

out the back door. As he passed the body of Bell, Gauss heard him say, “I’m

sorry I had to kill you, but couldn’t help it.” As the Kid went around the

building to the gate, with Gauss probably following behind leading a saddled

horse, the Kid came to the blood-soaked body of Olinger. Showing no remorse

as he had shown for Bell, he kicked the corpse and said “You’re not going

to round me up again!” The Kid mounted the horse with some difficulty on

account of his leg irons that were dangling from one leg and rode off. The

townsmen made no move to stop him, though they could have easily mobbed or

shot him to death, but instead they stood back and allowed him to escape. It

wasn't because they were “paralyzed with fear” as Garrett claimed, but more

likely, it was out of sympathy and understanding of Billy the Kid's

predicament.

|

*********************************** |

Instead of making a run for the border,

the Kid hung around in the county, dropping by on friends and telling them

about his daring escape from jail as if he had just come back from

vacation. His friends advised him to leave the territory, but the Kid was

confident he wouldn’t get caught and he told them he would first go to Fort

Sumner to get some money.

For the next two months the Kid hid out

at different locations in San Miguel County, but mostly in Fort Sumner.

There was a number of Billy the Kid sightings, but how many of them were

legitimate is up for debate. One thing was for certain, the Kid had returned

to his old haunts and was making no immediate plans of leaving New Mexico.

Meanwhile, Sheriff Garrett was doing a low

profile search for the Kid. Unlike before, he wouldn’t form a large posse,

nor would he even try to catch him alive. His plan was to sneak up on the Kid and

kill him. By early July, Garrett received word that the Kid was in or near

Fort Sumner and he may have gotten this tip from Pete Maxwell, the older

brother of Paulita Maxwell, one the Kid’s girlfriends. Maxwell didn’t like

the Kid around his sister, who was going to marry a prominent and wealthy

figure in New Mexico. So with information on the Kid’s whereabouts, Garrett

took John Poe and Kip McKinney with him; men he could trust to keep their

mouths shut and not question his actions, and he headed to Fort Sumner quietly.

It was July 14, 1881. The Kid was warned that the law was looking for him in

the area, so he hid out at a sheepherder’s camp. But by the afternoon or

evening, he decided to ride into Fort Sumner. Garrett had searched the area

and even sent Poe in town to

look around; becoming frustrated, Garrett was thinking about leaving (or he knew the Kid

was at the Fort and was just waiting for the right moment). The Kid, in

the meantime, was hiding in town unaware that Garrett was in the vicinity;

he visited with his friends and sweethearts, going from one house to the

other, but where exactly and with who he planned to stay with for the night is questionable.

|

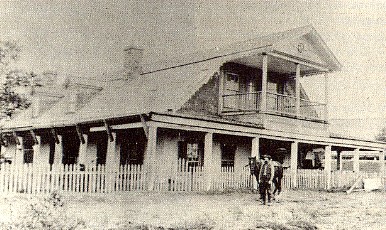

Pete

Maxwell's house (1882)

Photo from R.G. McCubbin Collection

Billy the Kid was shot and killed in Pete Maxwell's bedroom.

It's a bedroom that is entered from the side of the house (not in),

the first left corner room just beyond the gate and behind the

pillar.

|

It was getting late and the residents were

bedding down for the night, Garrett slipped out of the shadows and went to

Pete Maxwell’s house to ask him about the Kid. While Poe and McKinney waited

outside, Garrett entered Maxwell’s room and woke the sleeping man. At that

moment, the Kid, who was staying at a friend’s house, was getting hungry.

His host or hostess told him that Maxwell had butchered a yearling and for

him to help himself to it, and then bring the meat back and they would cook

it

for him. The Kid grabbed a butcher knife and stepped outside and walked

across the plaza to Maxwell's house. As he approached the porch, he

almost stepped over the two men who were sitting down outside Maxwell’s

room. The men rose and told the intruder not to be startled. The Kid didn’t

recognize the men and backed into Maxwell’s dark bedroom. Once inside he walked

over to the bed and in a low voice he said “Pete…Who are those fellows

outside?” Garrett was sitting at the foot of the bed and Maxwell lay still and

whispered, “That’s him.” The Kid walked closer to the bed and again asked

“Pete?” then he saw the silhouette of a figure sitting in front of him. The

Kid moved back slowly, and said “Quien es?” Garrett recalled in The

Authentic Life of Billy the Kid, “He must have recognized me, for

he went backwards in a cat-like movement, and I jerked my gun and fired.”

Garrett fired twice, the Kid fell to the floor, and then both Garrett and

Maxwell bolted out the door. The Kid was shot through the heart and gasped

for a minute or two and died. The men outside huddled outside the door and

heard the Kid’s death rattle. Certain the Kid was dead, Maxwell got a candle and the men

entered the room. They found the Kid lying on his back in the middle of the

room with a gun in one hand and a knife in the other.

This is the story that Garrett told and has been accepted, but did it really

happen this way? Was the Kid really armed or had his gun drawn? Since he

didn’t die right away, how come he didn’t shoot back or if the gun was in

his hand, surely the reaction of getting hit in the chest by a bullet would have caused the gun to go

off, but yet Garrett stated the Kid did not fire. Was it really coincidental

that the Kid walked in on Garrett and surprised him or was Garrett waiting for him? According

to McKinney, Garrett tied up and gagged one of the Kid’s girlfriends and hid

in the room and waited for him to walk in. I don’t know about you, but

something smells fishy. Considering Garrett’s earlier methods of dealing

with outlaws, which was by ambush, this incident probably wasn’t as “Kosher”

-if you will- as Garrett would want us to believe.

The residents were awakened by the gunfire

and walked out into the plaza towards Maxwell’s house. Upon learning that

the Kid was dead, men were shaking their fists at Garrett and women were

weeping. Garrett allowed the Kid’s friends to take his body across the plaza

to the carpenter’s shop to give him a wake. The next morning, Justice

of the Peace, Milnor Rudulph, viewed the body and made out the death

certificate, but Garrett rejected the first one and demanded another one be

written more in his favor. The Kid’s body was then prepared for burial, and

at noon he was laid to rest next to his two friends: Tom O’Folliard and

Charlie Bowdre.

New Mexico’s famous outlaw Billy the Kid, about nineteen or twenty years

old, was dead, but his legend was

born.

|

|

|

|

The gravesite of Billy the Kid in Fort Sumner

Webmaster's photo (2000)

The epitaph on the smaller gray stone reads:

BILLY THE KID

Born Nov 23 1860 Killed Jul 14, 1881

THE BOY BANDIT KING

HE DIED AS HE HAD LIVED

|

|

*********************************** |

After the Kid’s death, Garrett was viewed

with suspicion, though there were many who were grateful for Garrett riding

the territory of the famous outlaw, just as many felt it was foul play. To

win public opinion, Garrett, with the help of Ash Upson, wrote a biography

on Billy the Kid, and if one reads it closely, you can sense Garrett’s

remorse. Maybe he hoped writing the book would lift the dark cloud that hung over

him, which may be why Garrett portrayed the Kid as half Satan to make him a threat to society to gain reader’s support for his actions, and then

half Saint, to show his admiration for the Kid and how he was only doing

his duty in hunting the young outlaw. In the end, the book made a Judas

out of Garrett for going after his old friend and killing him. The biography

ended up turning Billy the Kid into a legend and Pat Garrett as the

villain. For the rest of his life, Garrett was haunted by a guilt

conscious, he would become uncomfortable when people asked him about the

killing, and he would later hint to friends that he wished he never took

the job to hunt down the Kid. This regretful behavior by Garrett

furthers my assumption that he planned out and ambushed the Kid in the

dark with Pete Maxwell's help.

History has been very unfair to Billy the

Kid. I don’t think any other western historical figure has had his name

dragged through the mud and represented so inaccurately and negatively. He

never robbed banks or trains like Jesse James. He never killed without a

probable cause like men such as John Wesley Hardin and Clay Allison. He

never was a large-scale rustler, raiding ranches and terrorizing the

inhabitants like John Selman or Jesse Evans. He never hurt, raped or

insulted women, nor harm children or the elderly.

But I’ll tell you who Billy the Kid was:

he was an orphan who unintentionally fell into outlawry, a lifestyle he

couldn’t get out of. He tried to make peace with the law and his enemies,

and both times it backfired on him, making things worse. He was never the

captain of the Regulators, but just another fighter. The Lincoln County War

itself would have turned out the same way, if he had never taken part in it.

He killed only in self-defense and during the war. The men he killed weren’t

angels, but were either bullies or outlaws, like the case of Morton and

Baker, who were both members of “the Boys.” The lawmen he killed were not honest

men trying to “protect and serve,” but crooked and corrupt. The Kid did

steal livestock, but in some cases he either paid for or returned what

he had taken. He even recovered stolen livestock for small ranchers and

judging by the poverty state he was always in, it seems he didn't steal enough.

I’m not saying Billy the Kid was an angel who

rode around with a halo over his head. He did do some wrong, but he was not

a Charles Manson of the 19th century. There were other outlaws

of his time who fit that bill, and that’s why no one today has really heard

of them, because they really were bad and not worth remembering.

In closing, I hope I have changed

someone’s perspective on Billy the Kid, from a dark villainous outlaw to a

misunderstood youth, an underdog, a rebel, a scapegoat and a good badman.

If you have read this whole

biography from beginning to end, I congratulate and thank you for your

time and patience, and most of all your interest to learn more about Billy

the Kid. Thank you for visiting my website and I hope you found it

informative.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bell, Boze Bob The Illustrated Life and Times of

Billy the Kid Second Edition,

Tri-Star-Boze Production, Inc. 1996

Nolan, Frederick The West of Billy the Kid

University of Oklahoma Press,

Norman 1998

Nolan, Frederick Pat Garrett’s The Authentic Life

of Billy the Kid, An

annotated edition with notes and commentary by

Frederick Nolan, University of Oklahoma Press, Norman 2000

Tatum, Stephen Inventing Billy the Kid:

Visions of the Outlaw in America, 1881-

1981 University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque 1982

|